Blocking a Payload of Death

By Paul Stanford

March 22, 1983

If anyone had told me a week before that I would be in a sheriff’s car handcuffed with a nun, on the way to jail, I probably would have told them they were crazy. But here it was really happening. I had just been busted for laying in front of an armored train that we believe was carrying over one hundred hydrogen bomb warheads to America’s newest nuclear nightmare, the Trident submarines.

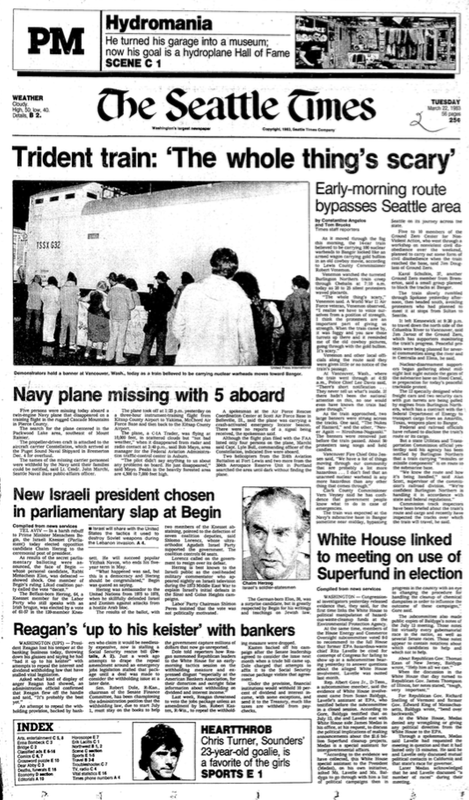

There were over 300 fellow protesters lining the last hundred yards of track leading into the Navy’s nuclear submarine base at Bangor, Washington, on the opposite side of the Puget Sound from Seattle. This was the end of the line. A line that stretched more than halfway across a continent, beginning from the ‘Pantex Corporation’ in Amarillo, Texas. Before the train had ever reached Washington State, thousands had demonstrated along the tracks, and more than a dozen had been arrested for trying to block its progress.

Many of those present on this day, March 22, 1983, at the Bangor submarine base were members of the local nuclear disarmament group, Ground Zero Center for Non-Violent Action. This same group organized a flotilla to blockade the trident sub, U.S.S. Ohio, when it first entered Puget Sound last August. Today they had a group of seven people who had been training together for three days on civil disobedience techniques. Each of the seven had written a couple of paragraphs to go along with the two-page statement that Ground Zero had prepared for distribution after the arrests.

I had first found out that this payload of death was traveling within 30 miles of my home just four days before. An article in a coastal Washington newspaper alerted me to Methodist minister Paul Jeffery, who was organizing a series of vigils along the railroad tracks in Elma, WA, a small logging town 40 miles from the sub base. I called him and found out he was affiliated with Ground Zero, and was, like myself, an Evergreen State College graduate (Evergreen is an alternative non-traditional college in western Washington). He had recently returned from his own personal fact-finding trip to Nicaragua. He promised to call me when the train arrived… and at 6:15 A.M., Tuesday morning, he called. The train would be in Elma between 8 and 9.

When I got there, a small crowd of 50 had already assembled on two overpasses above the tracks. Soon it swelled to a hundred and fifty, and when three TV helicopters and two planes started to circle overhead, I realized it wouldn’t be long before the train arrived. Five minutes later the train appeared. As it passed under us, we threw hundreds of origami does on top of the 12 low, snow-white cars that held the warheads, to symbolize our hope for a safer planet. As the train disappeared, I heard someone offer a ride to the Bangor sub station. Since my gas tank was, as usual, very low, I was quick to accept.

My benefactors were Fred and Sharon Ranevich of Elma. We had a good conversation on the way. I told them a bit about my history as a self-professed political radical, from anti-draft protests and D.C. smoke-ins, to working for Tom Hayden in Santa Monica the past summer. I also told them I wanted to stop this nuclear death train. Fred and Sharon were both good friends of the Methodist minister, Jeffrey, who had called. They have children older than me, but I could tell they were kindred spirits. Fred had even been jailed back during the Korean War for draft resistance. Little did I know that Fred and I were to be cellmates before the day was over.

The train’s entrance to the Navy’s nuclear submarine base at Bangor is hidden on a secluded arm of Washington State’s enormous inland waterway, Puget Sound. If a caravan of five or six cars hadn’t been ahead of us, I doubt if Fred, Sharon and I would have found it. But somehow about 300 demonstrators and 60 or 70 newspeople had managed to navigate their way here. We arrived with thirty minutes to spare, so I went and talked briefly with Jim and Shelly Douglass, a couple that helped lead Ground Zero. Jim and Shelly built their house so that the only thing between their home and the nuclear sub base gate is the train’s entrance. I also met a small but dedicated group who had followed the train almost a thousand miles to give us plenty of advance warning on its arrival. Soon the television planes and choppers were circling overhead again. The time had come; the end of the line.

When the train first appeared–its beacon shining in the sunlight, its horn sounding warning blasts–police, media, and we 400 protesters who had waited days for the moment seemed mesmerized. The train slowed perceptibly, but gave no indication it would stop.

Only about a hundred and twenty seconds passed from the time the death train rounded a bend till it disappeared into the submarine base. But for the people there, those two minutes were an eternity of action and drama.

The line of protesters, stretching down to the right of the tracks, did not move at first. Then suddenly, several groups of three or four persons proceeded towards the tracks. Kitsap County deputies were ready. They intercepted most of the demonstrators before they reached the tracks. Locking arms around them, the deputies held the protesters tight while the train neared.

Now that the deputies were occupied, I knew it was time to make my move. And so, to the inspiring cry, “YIP, YIP, YIPPEE!,” I lunged forward with my trusty sign, “We Want Jobs–Not Missiles.” Remarkably, I was able to weave my way through the ranks of deputies to the track the train was on. Only five other people made it that far. Quickly, I laid down and went limp. Seconds later, three deputies dragged me away from the tracks, about 20 feet in advance of the train.

Tension grew as moments passed. The crowd was pressing closer to the tracks, and deputies were shouting at people to stay back. There were shouts from the crowd. The group pushed forward as TV cameras and reporters closed in. Tempers flared as onlookers jockeyed for better viewing position. Slowly the train rumbled past.

And then it was all over. Groups of women, some crying, some consoling, knelt by the tracks and huddled together.

Out of the seven-person team that Ground Zero had organized to block the train, only four had made it to the tracks, and were arrested. Fred and I were the only others who made it. The six of us were led through the crowd to the waiting police cars. As we drove off, 300 people lined the road, waving, crying, and giving us thumbs up and peace signs. It was an emotional moment. The press quickly dubbed us the “Bangor 6.”

We were booked into jail and went to an arraignment five hours later. As we walked toward the courtroom, a group of about thirty people cheered their support as the TV cameras whirred. The courtroom was packed with reporters and well-wishers. We all pled not guilty to “attempting to block or delay a train,” a misdemeanor. And we were all released on our own recognizance. As of yet, the trial date of the “Bangor 6” has not been set.

Update: The trial has been set for May 19.

(This was published in the April/May 1983 issue of Overthrow magazine. – The story (not this article) was the lead on the national network TV news broadcasts, and made the front page of the New York Times.)

Update 2014: We were sentenced in 1983 to six months probation and a $100 fine. Later, protestors blocking the ‘white trains’ were charged with federal felonies and given much worse jail and prison sentences. On September 1, 1986, activist S. Brian Wilson was run over by a white train and lost his legs.